Craftsmanship of mechanical watchmaking and art mechanics

A crossroad of science, art and technology

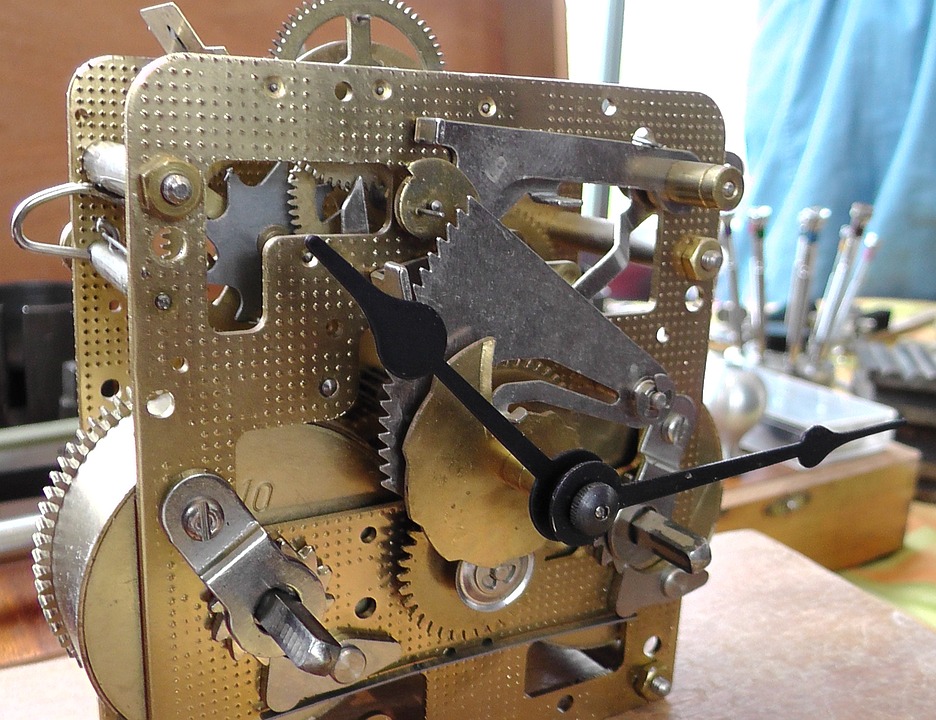

The craftsmanship of mechanical watchmaking and art mechanics is characterized by a combination of individual and collective, theoretical and practical knowledge and skills in the field of mechanics and micro-mechanics. These skills are used to create watchmaking objects designed to measure and indicate time (watches, pendulum clocks, clocks, chronometers), art automates and mechanical androids, sculptures and animated paintings, music boxes and songbirds. These technical and artistic objects have in common a mechanical device that generates movements or emits sounds. Although the mechanisms are generally hidden, they can also be visible, as in certain art automates or watch mechanisms whose visible movements contribute to the aesthetics and the poetic and emotional dimension of the objects.

Craftspeople are skilled in using the hand tools (which they sometimes make themselves), machines and nowadays digital techniques. In addition to technical ability, the practice requires patience, good eyesight and precision. The artisanal skills are based on a common historical foundation, and the same techniques, materials and tools are adapted according to the object the crafts-person wants to create.

Many jobs involved for many side activities

Today the watchmaking professions include production mechanic, poly-mechanic, production watchmaker, watchmaker (and clock-maker), micro-mechanic, external parts fitter, restoration-complication technician. Various specialists, such as stampers, lathe operators, pivot makers, dial makers, case makers and hands makers produce parts for watch mechanisms and watch covers. The watchmakers assemble the movements and finish them by polishing, adjusting and adding surface treatments. They also repair and restore watchmaking objects. Watch mechanisms are designed by watch design technicians, micro-technical engineers, prototypists and designers.

Music boxes are also made by specialists: the arranger transposes the melody, the drill operator makes the holes in the cylinder, the pin setter inserts the pins (metal rods), the grinder equalizes the length, the splitter creates the combs and the tuner files the combs until the desired note is obtained. Numerous complementary trades are involved in decorating mechanical art objects. Decorators use the skills of engraving, guillochage (machine engraving), enamelling, miniature painting, gem-setting, jewellery, leatherwork (bracelets), cabinet making, marquetry, feathering (songbirds), sculpture, make-up and sewing (automata).

A cross-border community linked with the watchmaking tradition

The watchmaking community is concentrated along the Jura Arc, including a few Swiss cantons and the French department of Doubs. The community specific to automates and music boxes (art mechanics) is concentrated in the Swiss canton of Vaud. The watchmaking and mechanics activity has left its mark on the architecture and town planning of all these regions. The towns of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2009 for their watchmaking town planning, and the built and technical heritage of the ‘Pays Horloger’ and the town of Besançon has been inventoried by the Inventory and Heritage Department of the Burgundy-Franche-Comté region (2013-2019).

With regard to the watch-making craftsmanship, there is a high degree of mobility of people, know-how and components within this area, which is characterized by a division of labour and a dense network of craftspeople, training institutions and small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as watchmaking groups, which are also essential for the perpetuation and transmission of know-how. While the know-how in mechanical watchmaking and art mechanics is primarily concentrated in the Jura Arc, artisanal watchmaking production does exist elsewhere in the world, for example in southern Germany, England and various Asian countries.

The Edict of Nantes as a starting point

Watchmaking developed in the Jura Arc in the 17th century, following the emigration of French Huguenot craftspeople after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. They brought technical know-how, capital and commercial networks. In the 19th century, manufacturing was traditionally based on the « établissage » system, in which the work was divided into small, specialized and widely scattered units, and the parts were then assembled when the product was finalized. Division of labor remains a feature of current practice. Inseparable from watchmaking traditions, the precision mechanics used in automates and music boxes developed in the early 19th century in the Jura mountains of the canton of Vaud.

A transmission done through many means

Skills are usually learned initially in training schools, and learning continues throughout the working life of the practitioners. There are five complementary transmission channels.

The institutionalized transmission of practical, theoretical and historical know-how takes place in public or private schools in initial training (in work study programs with workshops or full-time) and continuing education. Initial training lasts three to four years, with an additional several years of advanced training to become full-fledged watchmakers. The training provided by teachers, who are also practitioners, prepares learners for the various facets of the trades, from making tools to assembling components, drawing plans and repairing and restoring objects. To meet the needs of the watch industry, training courses are increasingly specialized and segmented, posing a risk to the transmission of craftsmanship skills and a global approach to the practice.

Special techniques, tips and tricks are also transmitted from peer to peer, be it from master to student or mutual aid between colleagues. Although until recently there was a culture of secrecy in the watchmaking world, it is gradually giving way to a more sharing environment. This informal transmission is particularly important when it comes to very specific skills, in particular art mechanics and restoration. However, this type of transmission may constitute a risk of loss of know-how due to the scarcity of certain specialists and students. The very small number of automaton makers and the even smaller number of music box restorers currently pose a threat to the perpetuation of these skills.

Watchmaking knowledge

Museums, libraries, archives and documentation centers are sources of information and inspiration for practitioners. They help transmit knowledge by conserving collections of objects, tools, machines and theoretical works, but also by documenting the items and producing publications. These resources are available to the public.

Knowledge is also transmitted by associations of enthusiasts and collectors who are used to sharing information. They disseminate and develop know-how by publishing journals, providing scholarships and organizing study trips.

At last, practitioners share their know-how via online blogs, forums and tutorials and collaborative open source projects. This mode of transmission reflects new and wider dissemination of practices, alongside the constant role of the media and specialized publications.

A social and economic regional importance

Historically, entire families were involved in watchmaking or music box assembly, developing apprenticeship practices in their families. The lifestyles of the inhabitants and part of their vocabulary (professional and colloquial) have been influenced by these activities. The craftspeople generally live in the buildings where their workshops are located, which, like the factories, feature large windows bringing light to the workbenches.

The development of know-how in mechanics goes hand in hand with the socio-economic development of the Jura Arc. The watchmaking community also contributes to life in society and in particular to dialogue between employers and workers. In Switzerland, in 1937, collective labor agreements were concluded, initially in the watchmaking and metalworking industries, thus establishing ‘labor peace’ marked by negotiations rather than confrontation. This model of partnership continues to exist in Switzerland and has left its mark on trade union and political history.

Today, summer holidays are still regularly modeled on the watchmaking holidays, namely the three-week summer closure of watchmaking workshops. It is also customary to give a watch, a music box or a small automaton on special occasions such as a birth, birthday or retirement. Finally, several expressions directly related to this craft for the inhabitants of the Jura Arc are still widely used: ‘on n’est pas aux pièces’ means ‘we’re not in a hurry’; ‘c’est réglé comme du papier à musique’ means ‘everything is in order’; ‘il faut remettre les pendules à l’heure’ means ‘set the record straight’; ‘tu as meilleur temps de’ is used instead of ‘tu ferais mieux de’ to mean ‘you’d better’.

Therefore, the inhabitants of the Jura Arc identify with and are proud of the traditions of arts and craftsmanship. For them, it conveys many socio-cultural values such as good workmanship, punctuality, perseverance, endurance, artistry, creativity, discretion, dexterity and patience. The infinite quest for precision and the intangible aspect of time measurement give these skills a strong philosophical dimension.

Why is it worth protecting

For its UNESCO’s enlistment, in 2020, in the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, watchmaking craftsmanship has been categorized as a « traditional craftsmanship », making it an important tradition to protect in France and Switzerland. Indeed, the design, execution and restoration of mechanical objects involve various trades related to technical and artistic creation. The bearers of the know-how are manifold and complementary. They can be grouped by areas of expertise, which may however overlap, as some craftspeople have know-how in several specialties.

In addition to the enlistment, which is a huge step in protecting the tradition, there are many actions done by professionals and watch-making lovers to protect the craftsmanship. For instance, as mechanical techniques are constantly evolving, researchers in the fields of micro-technology and materials help drive innovation, particularly through materials research. Museums, archives and libraries promote the historical and heritage dimensions of this tradition and provide information about the manufacturing principles.

RESUME

The craftsmanship of mechanical watchmaking and art mechanics is an ensemble of skills used to create watchmaking objects designed to measure and indicate time (watches, pendulum clocks, clocks, chronometers), art automates and mechanical androids, sculptures and animated paintings, music boxes and songbirds. Watchmaking developed in the Jura Arc in the 17th century, following the emigration of French Huguenot craftspeople after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. They brought technical know-how, capital and commercial networks. Skills are usually learned initially in training schools, and learning continues throughout the working life of the practitioners. While these skills have primarily an economic function, they have also shaped the architecture, urban landscape and the everyday social reality of the regions concerned.